- Home

- Strobe Witherspoon

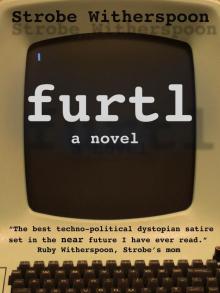

furtl Page 7

furtl Read online

Page 7

4.2

Northern Virginia in the summer was living up to its reputation as a muggy swamp, and Manny missed the crisp air of the Bhutanese mountains. His legs, sticking like plastic wrap to his jeans, left him longing for the days when he was unfettered by Western fashion norms. But even though an actual plan escaped him, he was still convinced that he could right the wrongs of his past. And that meant dealing with Virginia’s soupy summer months.

In a moment of impetuous curiosity, he decided to return to the Vault residences to have a look around. A part of Manny hoped to be discovered, freed from the self-inflicted identity purgatory that was his life.

Surely the Vault would have removed his retinal information from their database of approved residents, Manny thought, but to his surprise, Rob the entrance robot recognized his retinal scan and waved to Manny like he was competing in a robot beauty pageant – stiff combination half-wave and twist of his robot hand. Apparently, since Manny never officially divorced Mindy, his retinas were still considered acceptable for entrance into the community. At least that is what he told himself.

With Rob’s wave, Manny was allowed to penetrate an oasis of functioning infrastructure. Spruce trees blowing lightly in the odorless breeze. All the houses were in pristine condition. Manny noticed that some were two to three times the size they were when he left, and some were conjoined with the houses on either side of them. These were the new F, G, and H lines, the deluxe Vault homes.

Manny made his way to the driveway of his old house and walked to the door. His approach was slow and uncertain and his old stress habit of licking his lower lip like a windshield wiper returned. When a young couple answered, Manny felt a sense of relief come over him, but his heart also sunk a little. He told the couple – both adorned in diamond-encrusted crosses that were poking out of their matching pink polo shirts – that he was looking for the previous owner. Hunter and Haley Peabody did not seem to recognize Manny and offered up Mindy’s new address after Manny told them he had been trekking in the Himalayas for three years and had finally come across the ancient tai kwan yoga scrolls that Mindy had been looking for.

As it turned out, Mindy did not move far from their old home and was still living at the Vault. Her new address was only three blocks away.

To the west of the Vault, most of what was once Fern’s River State Park had been sold to the development. Restrictions were sidestepped by the Vault’s board of directors after multiple DCS employees living on the border of the park indicated they were interested in expanding their properties. The Virginia state government, citing budget shortfalls, held an auction for the land, and lots were sold to the DCS employees at bargain basement prices. The reason for the low auction prices was easy to explain: Nobody outside of the DCS was aware that the auction was occurring.

Soon after this expansion, properties on the other side of the community were mysteriously seized, reportedly due to continuous DCS infraction notices, otherwise known as “Culturally Reprehensible Activity Demerits” (CRADs). These penalties typically resulted in mandatory cultural education support classes and the seizure of property involved in said penalties. The most egregious offenders would receive “fulltime” cultural education, meaning their movement was limited to their home and CUS class until their “enrollment” was up and they had met the “requirements.” If the offender’s property was seized then dormitory housing would be provided for said offender. But don’t call it jail. If you did, your dorm stay would be doubled.

Activities that could result in CRADs ran the gamut from operating an unauthorized web cam portraying sexual themes to unauthorized chapter meeting of Planned Parenthood to unauthorized operation of an Islamic organization. Shielded by the opacities of the DCS tribunal system, the reasons for the penalties levied against the houses abutting the Vault residences were never released.

After news of the DCS expropriations started circulating through real estate circles, gated communities with ties to the DCS became the most sought after living environment for people of means. Communities with DCS “protection” shot up in value as most other non-gated properties declined precipitously, further depressing the already depressed housing market in Virginia.

Mindy answered the door wearing a light gray sweatsuit. When she saw Manny, the color in her face matched her sweatsuit. “Manny?” she said.

“Mindy?” Manny said.

“Manny?” Mindy said.

Mindy broke the cycle with, “What are you doing here?”

“I had to see you.”

“Manny…” Mindy said, interrupted by the sound of someone shuffling behind her inside the house.

“Who was that?” Manny asked.

“Where have you been?”

“I needed to figure some things out. After you left me, I needed to remember what was important. You want to know what I remembered?”

“What?”

“That you’re important. We’re important. Everything got so out of hand…I should have taken your advice.”

Mindy walked out of the house and closed the door behind her. “Let’s go to the backyard.”

Mindy and Manny walked the perimeter of the mansion in order to reach the backyard. The backyard was a paean to exotic exercise: a trampoline and trapeze rig inside of a swimming pool, gyroscopic orb simulators, climbing walls with randomized slope adjustment and weather simulators, and a petanque court.

“You’ve kept busy,” Manny said as the two sat down on a couple of balance balls that were neatly arranged on the Astro Turf stretching station.

“Ironman tri next month,” she said nervously.

Over the next half hour, Manny tried to describe the last six years of his life while giving his core a moderately strenuous workout. “And then I realized my time at the orphanage was over and I needed to return to fix the company that I broke.”

“Still trying to change the world,” Mindy replied.

“What else am I going to do with all this money? We can fix things.” Saying these things out loud to the woman who left him while sitting outside a house he didn’t recognize was difficult and confusing for Manny. Distance made his heart grow fonder on the one hand, but on the other hand his reasoning for said attachment became hazier.

Mindy listened, but Manny noticed a nervous air about her. “I’ve been thinking about what happened,” she said. “It was just a very emotional time and I wanted out. I think we both know that things weren’t working between us.”

“I know. I made bad decisions. I was too focused on my job and I didn’t put enough effort into us.”

“You realize I have a new life now,” Mindy said. As she said that, a figure appeared in the third floor window.

Manny noticed the figure. “And a new partner,” he said, looking at Mindy.

“A lot has changed. I can’t go back. So much has happened here since you left. This isn’t the same country.”

“I wanna fix that.”

“And here we go again.”

“What?”

“You can’t just let things be. You’re always obsessing about the next project.”

“You’ve seen what this country has become. Hijacked by the hysterical.”

“I know. That’s what I’m saying. The country’s changed. There’s no more money. There’s too many old people. They cost us too much. The government can’t afford them.”

“We can fix it.”

“No, we can’t. It’s everyone for themself now. You need to realize that.” Mindy turned around to avoid eye contact with Manny. She looked at a window in her house as Manny saw a shadow move behind the curtain. “You should go. I’ll walk you out.” Mindy was less confident than Manny had remembered. She carried herself with less certitude. Manny held out hope that her nervousness meant she still had feelings for him, but he really had no idea.

Mindy and Manny walked the five minutes back to the driveway in silence. “It was good to see you,” she told him when they stepped onto the concrete. But it

was obvious to Manny that she was eager for him to leave.

“Take care of yourself, Manny. If you need anything, let me know.” Mindy leaned over and gave Manny a soft kiss on his cheek. “I’m sorry I couldn’t help more.”

“I’m not ready to give up.”

Mindy gave Manny a slight nudge. Not a playful nudge, but a don’t-be-stupid-and-make-this-worse nudge.

“You’re still twice as strong as me,” Manny said.

4.3

Manny bought a used car with cash. The only place that sold used cars was called MOSTLY MONSTER TRUCKS! In the back of the lot, Manny found a Ford Badger, a grey four-door sedan with a listed price of $25,000. It was a reliable but poorly selling model — discontinued after two years — from the early Twenties.

The salesman at MOSTLY MONSTER TRUCKS! looked at him funny when he asked if they had any electric cars. “Never caught on. Too quiet.” The salesman also looked at Manny funny when Manny told him he would pay for the Badger in cash. “Fifty percent surcharge,” he told Manny.

“Fifty percent?”

“Yeah. List price is for fEPs only. Cash is 50% more.”

“Fifty percent?”

“Yeah. Ficktum surcharge.”

“Ficktum?”

“Surely you know about the FCTM.”

“Oh, the FCTM,” Manny said with faux confidence, not wanting to reveal his ignorance. He knew what fEPs were — Furtl Electronic Payments — because he was the creator of that retail proximity payment system. fEPs allowed an infrared device on one’s furtl phone, tablet, or watch to pay for a purchase at a cash register in under a second. When he left, fEPs were just catching on, capturing about 20% of all purchases. Cash transactions were around 30%, with credit cards representing about half of all purchases. But Manny didn’t know what the fCTM was and he wasn’t about to ask.

“Right. Okay,” Manny said, counting off another $12,500 from his wad of bills.

4.4

Driving around allowed Manny to survey a wider swath of Virginia. The nearby gated communities had become privatized mini-states. Uniformed militias patrolled the streets, the gates’ fortified titanium composite and the chain-link perimeter fences of days past replaced with electrified barbed wire atop concrete walls six feet high and four feet deep.

On one of Manny’s longer drives past the functioning gated communities and into the land of stillborn dreams, he came upon a large forested area in rural Virginia. There were a handful of abandoned houses and deforested plots of empty land peppering the horizon. The road that was built in 2016 to provide access to this notional community was sprouting weeds and potato chip bags.

This part of middle Virginia about two hours south of DC had sporadically seen attempts at development during the few recent short-lived real estate booms, but because of high building costs, poor demand for these properties, and lack of existing infrastructure, such places were now left for dead. The name given to this newly created municipality in 2016 was Fenston. The Fenston municipality filed for chapter nine (“municipal bankruptcy”) in 2022, when it could no longer service its debts and provide any public services. Thirty-eight US municipalities went bankrupt that year, the fourth worst year for municipal bankruptcies during the 2020s. Stripping these homes of their wood and copper wire and selling it on the side of the road to the drivers of passing monster trucks was one of the more reliable ways to make money for those living in this part of Virginia.

Manny noted that the garbage in front of one house was piled about five feet high and covered almost every inch of property. The tops of a few skeleton McMansions could be seen peeping over the hill of trash, the angled skeleton roofs rising above the garbage horizon like the beaks of a group of drowning wooden birds gasping for air. Manny noticed someone rummaging through the thick compressed garbage. At least it looked like rummaging. Upon closer inspection, Manny saw this lanky young woman, wearing a bright red bedazzled sweater with unicorns on it and a leopard print bandana, enter a code into a concealed keypad. A small part of the wall of garbage creaked open, and the woman walked into the property surreptitiously, looking about but failing to see Manny in his car. The garbage gate lumbered closed.

Manny climbed from behind the wheel and made his way over to get a better look. He reached the door in time to slip his foot inside and keep it from closing. Peering inside the property, Manny could make out a sprawling garbage filled fence that went a few hundred yards in each direction and covered the entire perimeter of a large piece of property. When Manny saw that nobody was watching, he nudged the door open just enough to fit inside.

As Manny looked around the premises, the garbage door closed and locked behind him, startling him. Nobody heard or saw him enter, Manny surmised. He then tiptoed further onto the property. The unfinished McMansions were organized in a hexagon shape down a small hill about 20 yards, and one dirt road led to an older 20th century ramshackle house in the center. Manny walked down the dusty road of the half-finished housing community, and when he was within a hundred yards or so of the houses he saw a number of tents. His curiosity piqued, Manny walked further inside the compound. As he neared the houses, he heard the buzz of human activity.

Manny crept to a window of the non-McMansion house in the middle of the hexagon and peered inside at what looked like a group meeting. A variety of individuals, young and old, sat in old wooden school desks. A woman at the front of the room gave a lesson on how to solder wires together, the chalkboard behind her full of instructions for what appeared to be the construction of explosive devices. These devices were primitive versions of some of the same devices Manny had researched in the early 2020s. The research was done at the request of the US government, who had contracted with furtl to create a way to detect explosive devices that were being operated remotely on the furtl network by environmental terrorist groups. Many such groups had been using these devices to blow up large residential and commercial developments at the time. This was one of Kurt Sturdoch’s first contracts with the US government. He was very proud of it. Manny’s “slippery slope” concerns about this type of work fell on deaf ears with the board. Indeed, Manny’s reservations were voiced with little vigor, as even he was excited by the financial windfall that this contract would bring to furtl.

Manny leaned closer to listen to the class, unaware that a man had crept up behind him. The man raised a brick and hit Manny over the head, knocking him out.

4.5

Manny awoke, groggy, to the sound of ambient Indian acid jazz music in the background. He was sitting in a bean bag chair, his hands tied behind his back. Most of the paint on the walls had chipped away in this small room that was made even smaller by the plethora of world music instruments and unconventionally shaped lamps. A number of scented candles competed for Manny’s nostrils’ attention. An affable-looking older man with a bushy beard and thinning pony tail was sitting in a small chair next to a door. He noticed Manny was awake and knocked on the door.

A female in her mid-30s entered. She was dressed in tight black jeans, black spectacles, and a sleeveless black T-shirt that showed off her spindly arms. A younger man and woman entered behind her. Manny recognized the young woman as the person he followed into the compound. The man holding her hand was dressed like 1992: flannel shirt tied around the waste with big baggy T-shirt, ripped jeans, and Doc Marten boots.

The woman in black walked up to Manny. “Who do you work for?” she asked.

“I don’t understand,” Manny replied, still hazy from the head trauma.

“Don’t play stupid,” she said.

“I was just curious.”

“Bullshit,” the other woman barked. “You followed me here.”

The woman in black held up her hand to keep the other woman quiet. “I will ask you again. Who do you work for?”

“Nobody.”

“C’mon, you’re a hired thug of the Corcoran administration,” the young woman said. The woman in black held up her hand, exercising her authority to silenc

e this woman.

“I have been in the mountains of Western Bhutan for six years working in an orphanage.”

“Sìg hêe pe chê ong líng èk páa?” (“What was the name of the orphanage?”) the woman in black said, surprising the entire room with her Tchanchzka proficiency.

“Dtàg khng jìt in-yan,” Manny said.

“The sixth window of spiritual prosperity?” the woman in black asked in English. This was followed by “knung bhê n kng?” (“The one at the base of the Maapurnauma range?”)

“Kh me tê aát an ní-rn kng se com-po,” Manny said. He knew she was trying to trick him and he told her in Tchanchzka, “No, that’s the third temple of eternal carnation.”

“You know your Western Bhutanese orphanages.”

The young woman at her side was confused. “Francesca, how do you–”

“My senior thesis at Brown was on the semiotics of 16th century Western Bhutanese displaced populations. I spent a summer there doing research. Changed my life. Met a young rice herder name Boonie,” Francesca said with an air of resignation. Her eyes drifted off.

“Boonie Mapalaweya?” Manny asked.

“You know Boonie?” Francesca said, unable to control her excitement.

“I do,” Manny said.

“Oh my goodness, what is he up to these days?” Francesca asked.

furtl

furtl